Biodiversity, a cornerstone of ecosystem services, is under threat due to human activities like land use changes, resource exploitation, and climate change. Organisations are both contributors to and victims of biodiversity loss, facing significant risks including water scarcity and regulatory changes. With global regulatory pressures increasing, organisations must now account for their biodiversity impacts.

Natural Capital at Risk: Biodiversity risks, regulation, and steps forward

A species sprung from nature

Nature is an excellent provider of services that are essential for our human society. Air and water purification, provisioning of food and resources, climate regulation, and recreation. An essential backbone of these services, often referred to as ecosystem services, is the complex topic of biodiversity or (as defined by the European Environment Agency) “…the variety of ecosystems (natural capital), species and genes in the world or in a particular habitat.”

As a species sprung from, a part of, and dependent on nature, we are also ultimately affecting it (see also this RiskSphere article on biodiversity: The Planetary Garden). Since 1970 we have witnessed an on average 69% decline in global populations of mammals, fish, birds, reptiles and amphibians, and one million animal and plant species are now threatened with extinction. Roughly 66% of the ocean environment has been significantly altered, and more than a third of the world’s land surface and nearly 75% of freshwater resources are now devoted to crop or livestock production. Research has also concluded that the health of our ecosystems is deteriorating more rapidly than ever and that the places with the highest expected impact tend to be the home of indigenous peoples and some of the world’s poorest communities.

Organisations in the ecosystem

Organisations play an essential role in our civilisation and from the perspective of the double-materiality concept we can observe how organisations affect and gets affected by nature.

According to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), organisations affect nature and biodiversity through impact drivers (also called direct drivers or pressures) which can, on a general level, be divided into:

- Land and sea use change

- Exploitation of natural resources

- Climate change

- Pollution

- Invasive alien species

Even though impact drivers can be detrimental to our ecosystems and in extent our global society, the underlying economic activities that cause them are an integral part of human activities, our existence and wellbeing. Hence, we are faced with the intricate and complex task of mitigating the change while adapting to the new world we are creating.

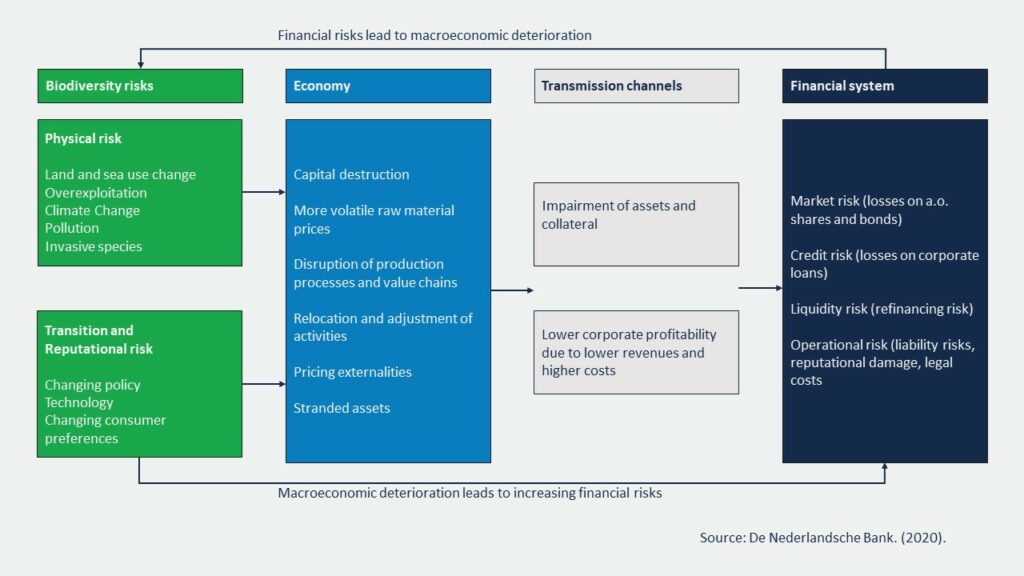

Physical risks and Transition risks

Organisations’ exposure to biodiversity risk can be broadly divided into two broad risk categories physical risks (e.g. water scarcity, crop yields, desertification) and transition risks (regulation, financial markets, customer reputation). For organisations in the financial sector, these risks are aggregated and transmitted through second order effect, e.g. in an equity portfolio or a loan portfolio. How these risks transmit through the economy (companies, organisation, and governments) to the financial system (banks, asset managers, and financial institutions) is illustrated in the diagram below (note here that although classification and transmission channels are comparable to climate risk, biodiversity risk is a district risk category):

Organisations’ exposure to biodiversity related risks are vast and present on a global scale. In The Netherlands alone it has been estimated that Dutch financial institutions have a €510 billion exposure to biodiversity risks. Within the euro area, approximately 72% of companies are highly dependent on at least one ecosystem service, exposing them to biodiversity risks. On a global level, it has recently been determined in The World Economic Forum (WEF) 2024 Global Risk Report that biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse are regarded as existential global threats.

A changing regulatory environment

Regulation is one transition risk that has become more present in recent years with the increased political sustainability ambitions. During the COP 2022, nearly 200 governments agreed on an ambitious agenda with 23 targets to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030 in the form of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF). The framework calls on nations to establish disclosure requirements, target setting, and the alignment of incentives, and countries are now expected to revise their National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) in alignment with the framework. It is from this backdrop that regulators all around the world are increasing the requirements and demands on organisations.

The European Union, for example, has in this context published a 2030 Biodiversity Strategy and increased the nature reporting requirements through the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which will eventually apply to an estimated 50,000 companies. Alignment and best practice initiatives have also appeared on a global level, for example the market-led Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD), the voluntary reporting standard Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and the Partnership for Biodiversity Accounting Financial (PBAF). This changing regulatory landscape is going to put further pressure on organisations and their biodiversity risk ambitions.

Quantifying the unquantifiable

What organisations can do on practical level is to begin accounting for biodiversity risks and to establish how biodiversity is affected by the organisations economic activities and how this corresponds to the organisation’s risk exposure. It is important to keep in mind that the economic activities related to the organisation can be extended beyond geographic location, jurisdiction, and sector through its stakeholders, counterparties, and supply chains.

A useful framework to utilise is the LEAP approach developed by TNFD. In short, the LEAP approach consists of the following steps:

- Locate: identification and mapping of geographical areas where the organisation interacts with natural ecosystems.

- Evaluate: assessing the organisations dependence and impact on these natural ecosystems (the double materiality concept).

- Asses: determining and analysing the related risks and opportunities connected to the organisation’s dependencies on these natural ecosystems.

- Prepare: developing and implementing strategies to mitigate risks and take advantage of opportunities related to these natural ecosystems.

Tools and methods for the LEAP approach

There are today various tools and methods that can be used throughout the four steps in the LEAP approach.

EEIO (Environmentally Extended Input-Output)

One avenue is to directly translate monetary flows into impact drivers, quantitative measures per pressure factor and KPIs. This can be done though Environmentally Extended Input-Output databases such as ENCORE and Exiobase which provide extensive data on economic activities and revenues streams and how these translate into impact drivers via materiality heat maps.

Geospatial data

Another avenue is the use of geospatial data or satellite data to determine ecologically sensitive areas and to measure the impact on a geographical location that an organisation can have over time (e.g. deforestation, desertification, construction, and pollution). Geospatial data can be accessed through open platforms and via data providers.

Screening tools

There are plenty of complementary tools for assessing high level risks on individual companies and portfolios based on location, sector, and supply chain (resources). Some examples are listed below:

- WWF Biodiversity Risk Filter

- TNFD Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool (IBAT)

- SBTN High Impact Commodity List

- SBTN Materiality Screening Tool

“But what about metrics?” – the quant asked. In contrast to climate change, which has the associated and convenient carbon dioxide equivalent as the metric of choice, biodiversity is dependent on various metrics which can be used in different situations depending on perspective. One recurring metric is hectares, which can be used to determine changes in the geographical location, for example when using geospatial data. However, this is not always suitable when for example assessing impact drivers through supply chains or pollution. Hence a holistic approach which encompasses different metrics is essential.

Reach out for tailored advice

Partner with RiskSphere to navigate the complexities of biodiversity risk and develop tailored strategies that align with your organisation’s unique needs and regulatory requirements.

Contact us