Climate change isn’t waiting for 2050. It’s already reshaping where we live and how much we pay for it. When we talk about climate risk, there is a tendency to talk about long term risks. Indeed, many of the expected worst-case scenarios are still to materialize unless we manage to collectively transition away from the carbon-based economy. However, some concerning effects of climate change are already present. One area where this is getting more apparent is within the real estate sector. Houses are immobile and are therefore fragile to drastic changes in the landscapes in which they are situated, such as droughts, wildfires, and floods. The impact on housing is direct and more visible than in other sectors, where risk might be driven by second or third order effects such as within food supply, infrastructure, and energy production. Indeed, it is hard to argue about climate risk when your basement is full of water following that supposedly once in a one-hundred-year rainfall that now occurs every decade.

How Climate Change is Shifting the Housing Market

Flood Risks and the Housing Market

Let us focus a bit on flood risk (one example of physical climate risks). It has been estimated that about 23% of the global population is directly exposed to flooding of more than 0.15 metres (World Bank, 2020). Houses tend to be built along coasts, on riverbeds, and in other areas that are susceptible for floods. Sea level rise can be expected on a longer time horizon because of melting ice sheets, while disrupted precipitation patterns (rainfall) is already causing problems on an increasing scale globally.

Flood Risks in the Netherlands

Flood risk in the Netherlands is obviously not a new thing. For a country with 26% of its surface below sea level, there is to some degree already a mindset (as well as dikes, canals, and pumps) in place to deal with the risk of floods. An example of this can be found in one of RiskSphere’s clients, a Dutch promotional bank, which was founded on the need for flood risk reduction and water management after the devastating North Sea flood in 1953. The Netherlands, however, is quite unique in this regard. For another country, say Sweden, increased flood risk requires a new way of thinking. In contrast to the Netherlands, Sweden has seen a land rise (post-glacial rebound) as a remnant of the large ice cap that covered the Nordics and Northern Europe more than 10 000 years ago. Hence, flood risk, apart from some rare heavy rainfalls, has not really been on top of minds of Swedes. Until now.

A new way of thinking

A sign of this change appeared by the end of last year when the Association of Swedish Real Estate Agents came out with a report and a stark warning that homeowners should expect that the value of their homes will be increasingly affected by climate risks, floods among others. It was also concluded that the structure of the current home insurances is not fully taking these risks into account, something which in the future could spur higher insurance premiums for houses in affected areas, or in rare cases even making houses uninsurable (Mäklarsamfundet, 2024). Another sign came earlier this year when the Swedish government concluded an investigation on climate change adaptation (adapting to climate changes by reducing the subsequent risks). Apart from suggestions regarding policy changes covering the disclosure of climate related risks for different areas, as well as the potential prohibition of construction in the most risk prone areas, the investigation contained some interesting remarks on the financing aspect for risk reduction measures. It was suggested that homeowners might need to contribute to the financing of climate change adaptation measures with a value of up to 10% of the market value of the house that would benefit from the protection. Something, they conclude, which could change how real estate valuations will be conducted in the future (Government Offices of Sweden, 2025).

The example is country specific for Sweden, but considering the devastating floods seen in the past years in, among other place, Germany, Spain, and Slovenia, similar suggestions should be expected in other nations as well and for other risk categories such as droughts and wildfires.

Other Climate Risks

Let us now move across the pond. Following the horrifying wildfires of California earlier this year, it became clear that more than 10% of the homes in the affected areas were estimated to have had their home insurances cancelled prior to the wildfires. This as large insurance companies have exited the market due to an increase in estimated wildfire risk (evidently a correct analysis) which could not be reflected in the insurance premiums, hence making the insurance cover not economically viable for the underwriter. There are also indications that 40-80% of the wildfire survivors are underinsured, and recently some home insurance premiums have also increased drastically in the aftermath of the catastrophe (San Francisco Chronicle, 2025).

An increase of Risks

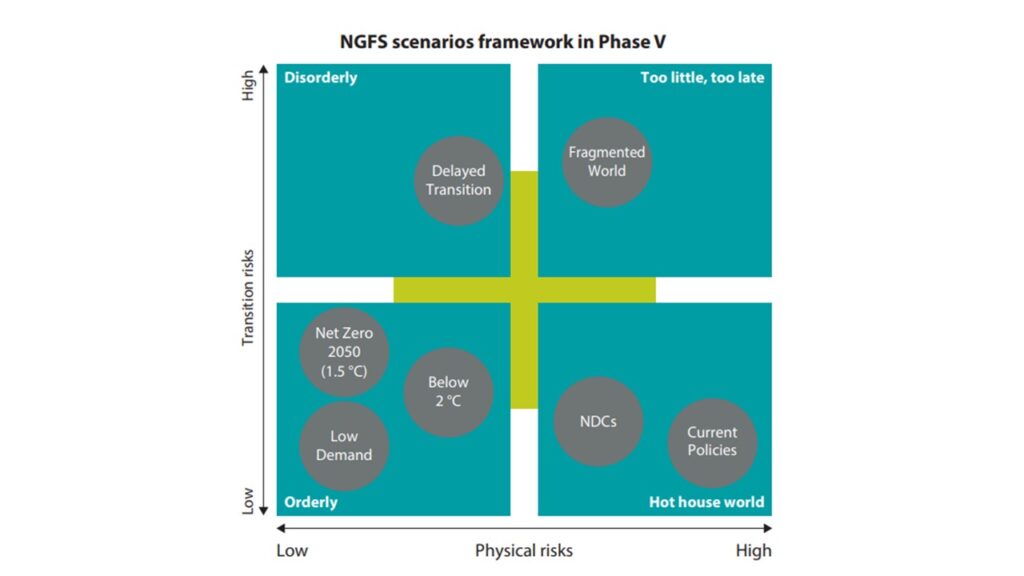

An increase of physical risks means that climate change adaptation will become more acute, and for immobile (and often highly leveraged) assets such as real estate, which already tend to be located in risk prone areas, this is especially concerning. As one could argue that the current global trajectory is increasingly moving towards the right-hand side of the Figure above, this increase in physical risk should with time also be reflected in the housing market. However, in a curious article from 2020, some researchers showed that climate change only affect real estate prices in neighbourhoods which are predominantly inhabited by people who believe in climate change and not affected in neighbourhoods predominantly inhabited by climate change deniers (Baldauf, Garlappi, 2020). These results might hold true in a world with lower physical risks but should reasonably change as physical risks increase. Again, the water in your basement does not care if you believe in climatology or not.

At the end of the day, someone is going to have to pay the bill for climate change adaptation measures. Perhaps more countries will follow the Netherlands with the creation of their own public water banks (or why not drought banks, or wildfire banks). This however would require some political leadership, so the more probable scenario is that the homeowners themselves will have to foot the bill once market forces kick in, or rather, continues to kick in. If it will be via fees taken out by municipalities as currently being discussed in Sweden, or via high insurance premiums as in California, remains to be seen. Most likely there will be a whole spectrum of solutions. What is clear though, once the market fully takes these risks into account, some fluctuations in real estate prices should be expected.

Markets will have to respond

As physical climate risks materialize markets will have to respond. In the coming years one should expect and be prepared for some volatility in the price of, not only real estate, but commodities, energy, and other financial and non-financial assets. At RiskSphere, we understand systems thinking and the second- and third-order effects of climate risk. We work on both climate change mitigation and adaptation from a risk management perspective with a wide range of organisations globally. In Africa, for example, we are supporting central banks and financial institutions in Rwanda, Angola, and Mozambique to integrate climate risk into financial policy, stress testing, and investment frameworks. Whether for countries, financial institutions, or businesses, we help translate climate risk into action and opportunity.

Reach out for tailored advice

As climate risks begin to reshape real estate markets, understanding their financial impact is more critical than ever. At RiskSphere, we help organizations turn climate risk into actionable strategies — from property valuation to policy planning — ensuring you're ready for what's next.

Get in touch