This article highlights the evolving role of the financial sector in the current climate crisis and its potential in a post-growth economy. It emphasises the need for the financial sector to expand its fiduciary duty and contribute to a sustainable future by aligning with planetary boundaries and promoting positive social impact.

Degrowth: Finance’s secret weapon against climate chaos

Climate alarms reshape the financial sector's role

Climate change has risen rapidly in the political agenda in recent years, but whether this will lead to timely changes is still to be seen. The recent series of record braking high temperatures, wildfires, and monsoon rains serve as a confirmation of the impact of human activities on the environment. These events also serve as a warning about the severe consequences if ambitious GHG emission reduction goals are not achieved.

On the one hand, this has led to new and stricter regulations on the real economy and the financial sector, and to a rise in social awareness and unrest, on the other. While the stronger focus of regulators to address the climate crisis is certainly a good sign, a significant percentage of civil society and academy is demanding stronger measures.

The EU has prioritised the development of a regulatory context for the financial sector to address climate change. This has been the result of its Green New Deal aiming to channel private investment to support the transition towards a climate-neutral economy. For some, these new regulations are falling short in addressing the elephant in the room, the paradox of aiming for infinite economic growth in a system with finite resources, the Earth. While this triggers discussions that go beyond this article’s purpose, addressing this topic serves as a reference to discuss the potential of the financial sector to deliver significant impact by expanding the scope of its fiduciary duty.

Limits to growth and post-growth alternatives

The current economic model uses GDP growth as the primary goal to promote development, this has led us to our current status of environmental degradation and social inequality. Critics have been questioning the inconsistency between this growth obsession and the existence of planetary boundaries for over fifty years, even before climate change was widely acknowledged as a hazard to be prevented.

Since the publication of ‘The limits to Growth’ by MIT scientists in 1972, several approaches have emerged proposing a change in the focus of the current economic model (see table below). Post-growth alternatives propose to widen the scope beyond GDP and emphasise the environmental impact of the economy and the social wellbeing that would lead to a fairer society. This entails redirecting capital away from sectors that promote inequalities and environmental degradation and channelling them into areas that strive for a resource equilibrium that uplifts marginalised segments of society.

In the meantime, the increased occurrence of extreme weather events confirm that not enough has been done to address the climate crisis and the consequences are becoming more material. During the last decade policymakers have produced an adjusted economic model that confronts its environmental constraints, ‘green growth’. In the EU this model is known as the Green New Deal, the regional approach towards a system that meets GHG emission goals and prevents an increase of world temperature above 1.5 degrees in relation to the pre-industrial times.

The goal of this economic model is to promote a sustainable economic growth through technical innovations (read renewable energy, electric vehicles, carbon capture technologies) that allow to decouple growth from resource use and its environmental impact. While this might appear as a sound approach, evidence shows that it is far from achieving its objective.

Investments in green technologies have not resulted in a net reduction in total emissions but translated into an increasing demand for a new set of resources. While more sustainable energy is being produced than ever before, the global picture shows that we are still on track to overshoot several planetary boundaries.

In many cases, new infrastructure for renewable energies has increased the power capacity without substituting conventional energy sources that contribute to global warming. On the contrary, these investments have translated into higher resource use rates, in electric mobility and industry in general. This phenomenon is known as Jevon’s paradox, when the increase in efficiencies leads to a higher level of consumption, not a lower one. The limited progress made to keep global temperature within reasonable level invites us to consider other strategies that lead us through a safer pathway.

A post-growth future in the making

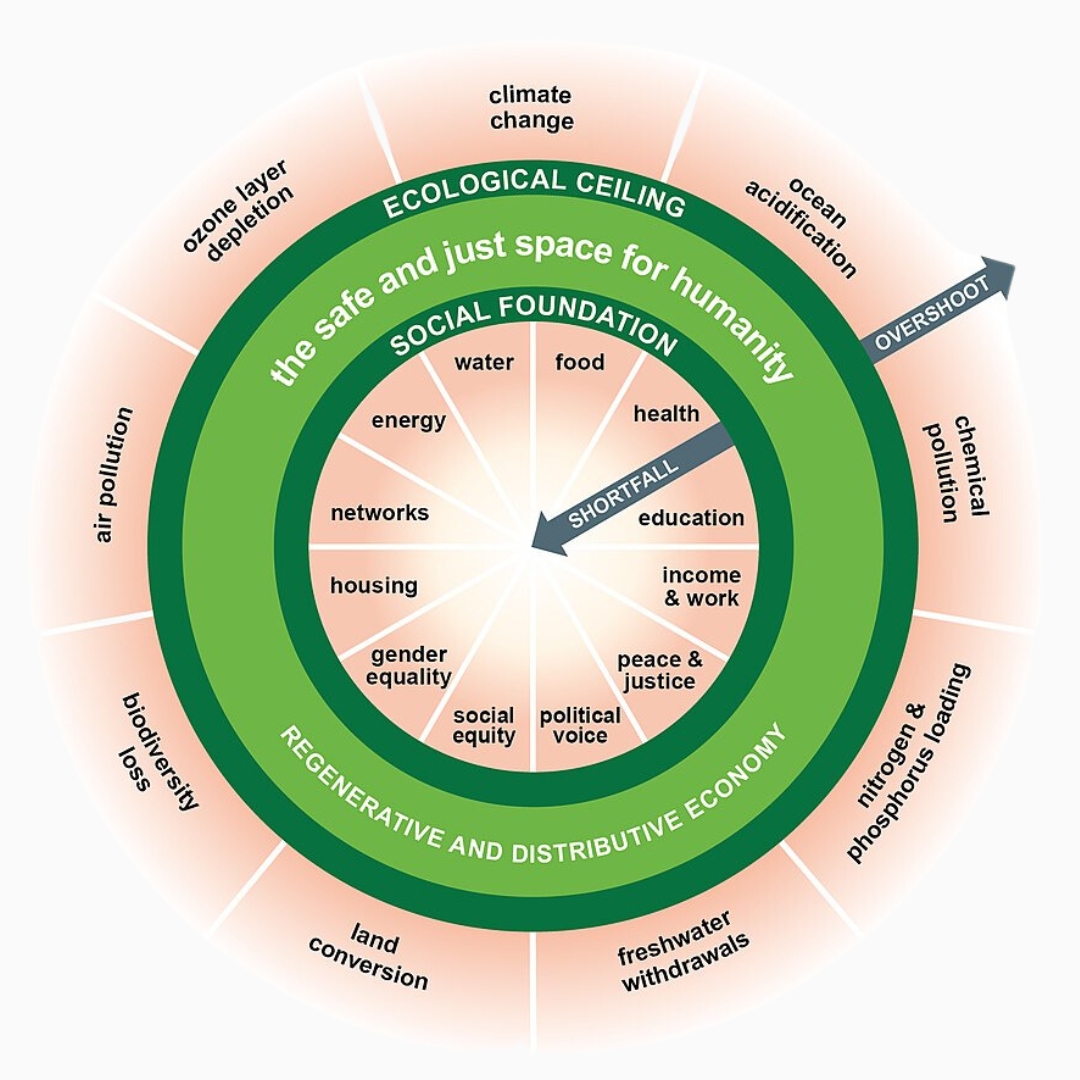

One of the alternative approaches that has gained more traction is Kate Raworth’s proposal of Doughnut Economics, which encourages seeing the economy as embedded and dependent upon society and the environment. This implies acknowledging that there is an ecological ceiling to growth, while setting a social foundation that ensures that no one lacks life’s essentials.

The Doughnut framework proposed by Kate Raworth

Source: Kate Raworth, (2017). Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist.

We are currently overshooting seven of the eight key planetary boundaries that measure environmental health and are still far from accomplishing the SDGs which broadly capture the social foundation that Raworth proposes. Cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen have already taken distance from the growth imperative and are working on the adoption of this model. However, a wider influence on global policy is still to be seen.

The financial sector can bridge growth and sustainability

While the discussion about bringing post-growth alternatives into practice is still open, the financial sector has a central role in these discussions. Financial institutions provide the resources that lead to economic expansion; therefore, they have the potential to nudge the real economy in a trajectory within the planetary boundaries and generate social value. The EU has taken some important steps in this direction through instruments such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), and the EU Taxonomy.

These instruments promote greater transparency in relation to sustainability risks, and the provision of sustainability-related information for investors. However, they constitute only the basis for financial institutions to translate the adaptation and mitigation strategies that address climate risks, into opportunities that deliver positive impact by redirecting capital into the right ventures. Going one step further implies reevaluating the fiduciary duty of the financial sector, ensuring the investors’ best interest by complementing returns with climate and social action.

“The current climate crisis is taking the financial sector from pursuing risk-adjusted returns towards risk-adjusted and impact optimised returns.”

We guide you through this transition

At RiskSphere we encourage our clients to pose ambitious questions like the ones shared in this article. We want to be triggers of change by using tools like climate risk stress testing and scenario analysis to shape a value-driven strategy within a context that requires complex decisions.

We do not believe in one-size-fits-all solutions, we work together with our clients’ team to address what is most important for them while adding to their unique identity. Our goal is to achieve unprecedented ESG excellence, creating a global ripple effect for a sustainable future. Contact us to become an organization that adopts sustainable practices to have an impact across the sphere.